Notes on Consistency

- Consistency mean a read from a system should return the latest write.

- This can be achieved using various kinds of locking mechanism in case of a single node multi-threaded mechanism. All threads can be synchronized because they share the same clock.

- In case of distributed system, where a global clock is not available, we need to figure out what the latest write was, to make the read consistent.

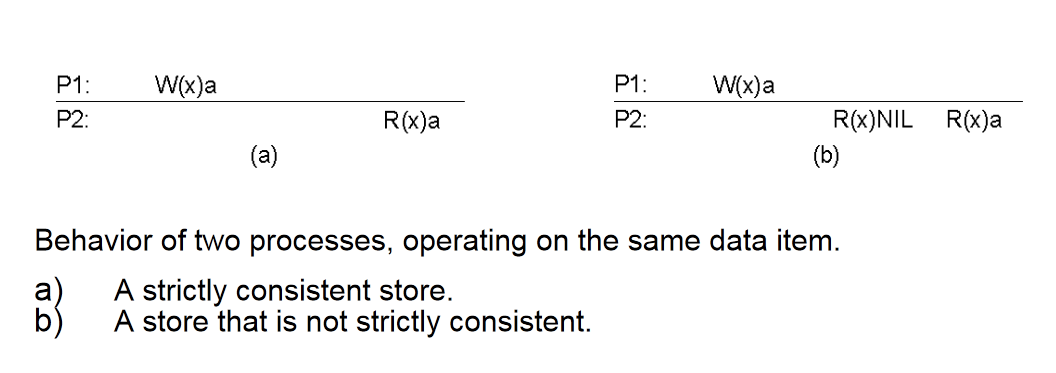

Strict Consistency

- Strict consistency is the strongest consistency model.

- Under this model, a write to a variable by any processor needs to be seen instantaneously by all processors.

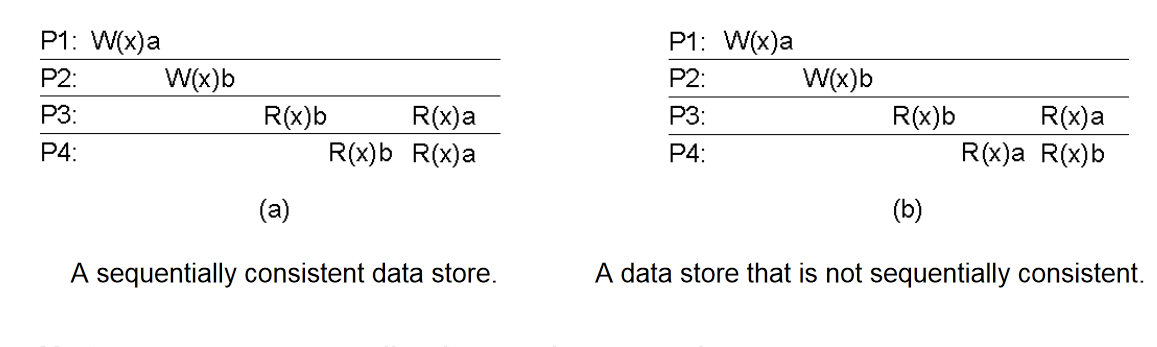

Sequential Consistency

The result of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program.- Leslie Lamport- What the above statement means is, that, for each thread, operations need to happen in program order. A thread

T1with operationsA1,B1andC1will have to execute these operations in that sequence. Across multiple processors, the sequence is undefined. ThreadT2with operationsA2andB2, can be scheduled in anyway with respect to threadT1as long asA2andB2maintain their mutual order between themselves.Sequential consistency gaurantees Program Order. - A process in a sequentially consistent system may be far ahead, or behind, of other processes. For instance, they may read arbitrarily stale state. However, once a process A has observed some operation from process B, it can never observe a state prior to B.

- In the image below, write from P1 and P2 may be scheduled in any order amongst themselves, but once an ordering has been decided, P3 and P4 should see them in the same order.

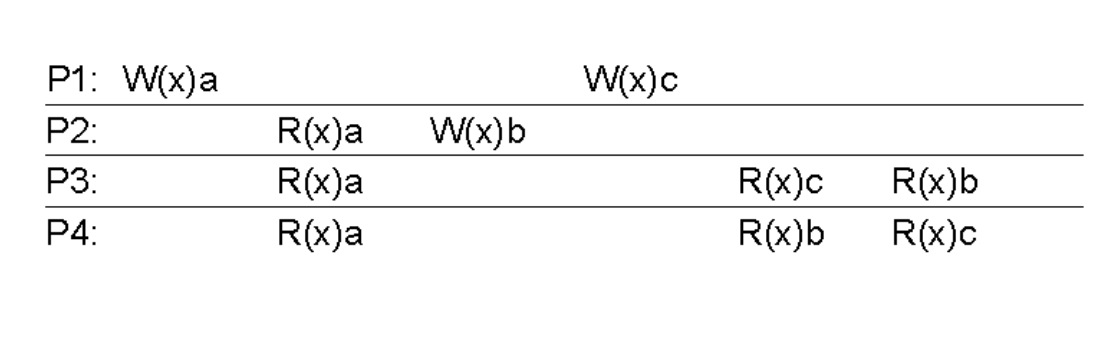

Causal Consistency

- Causal consistency can be defined as a model that captures the causal relationships between operations in the system and guarantees that each process can observe those causally related operations in common causal order.

- If there is an operation or event A that causes another operation B, then causal consistency provides an assurance that each other process of the system observes operation A before observing operation B.

- Causal consistency stems from Lamport’s definition of the happens-before relation, which captures the notion of potential causality by relating an operation to previous operations by the same process, and to operations on other processes whose effects could have been visible thanks to messages exchanged between those processes.

- Causal consistency is a weaker consistency model than Sequential consistency, because Sequential consistency expects all processes to observe not just causally related writes but all write operations in common order.

- Causal consistency is stronger than PRAM consistency, which requires only the

write operations that are done by a single process to be observed in common order by each other process. - *It follows that when a system is sequentially consistent, it is also causally consistent. Additionally, causal consistency implies PRAM consistency, but not vice versa.

- Write operation

W(x)2is caused by an earlier writeW(x)1, and it means that these two writesW(x)1andW(x)2are causally related as processP2observes, reads, the earlier writeW(x)1that is done by processP1. Thus, every other process observesW(x)1first before observingW(x)2. - Also, another thing to notice is that the two write operations

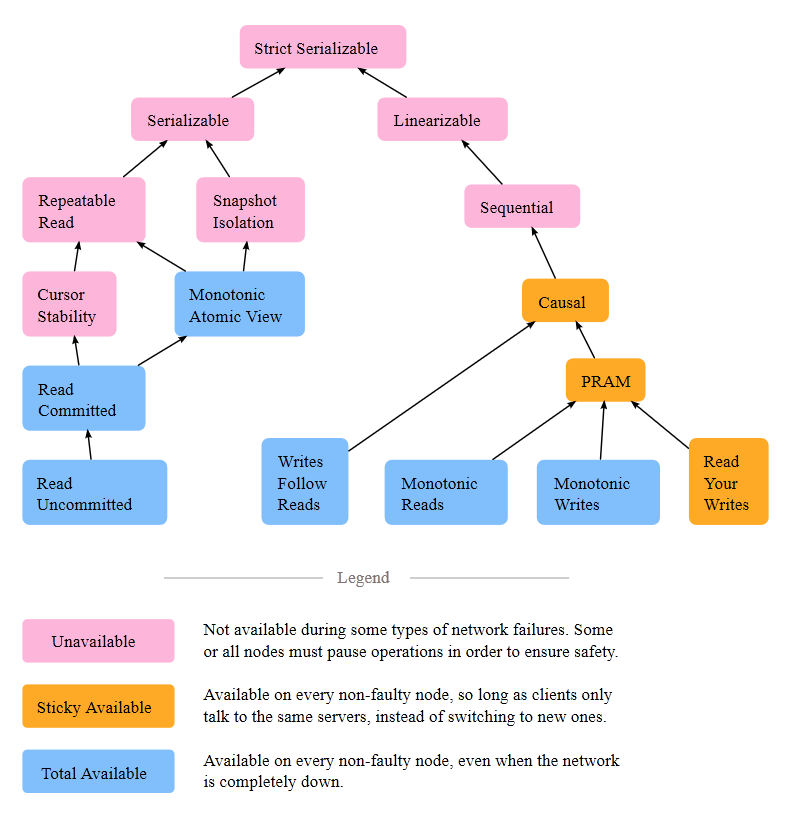

W(x)2andW(x)3, with no intervening read operations, are concurrent since processesP3andP4observe, read, them in different orders. - There are four different session guarantees that are ensured and guaranteed by the causal consistency model. Those guarantees are summarized below (note that by session, we basically mean a process that is interacting with the datastore from where data is being read and written to):

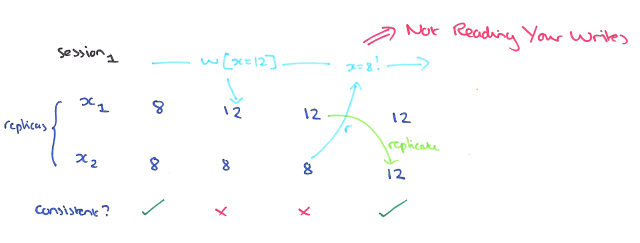

Read Your Writes

- This means that preceding write operations are indicated and reflected by the following read operations.

- The Read Your Writes guarantee ensures that whenever a client reads a value after updating it, it sees that value.

- If a process performs a write w, then that same process performs a subsequent read r, then r must observe w’s effects.

- Note that read your writes does not apply to operations performed by different processes. There is no guarantee, for instance, that if process 1 writes a value successfully, that process 2 will subsequently observe that write.

- Read your writes is

sticky available, ie, if a network partition occurs, every node can make progress, so long as clients never change (stick to) which server they talk to.

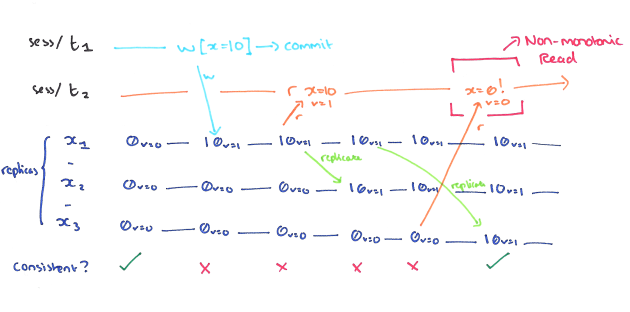

Monotonic Reads

- This implies that an up-to-date increasing set of write operations is guaranteed to be indicated by later read operations.

- A non-monotonic read anomaly occurs within a session when a read of some object returns a given version, and a subsequent read of the same object returns an earlier version.

- If a process performs read r1, then r2, then r2 cannot observe a state prior to the writes which were reflected in r1; intuitively, reads cannot go backwards.

- Monotonic reads does not apply to operations performed by different processes, only reads by the same process.

- Monotonic reads can be totally available: even during a network partition, all nodes can make progress.

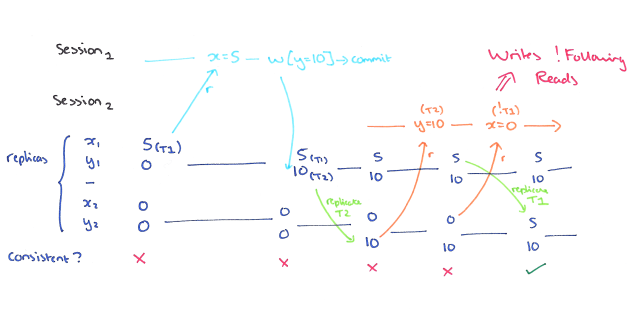

Writes Follow Reads

- This provides an assurance that write operations follow and come after reads by which they are influenced.

- A non-monotonic transaction anomaly occurs if a session observes the effect of transaction T1 and then commits T2, and another session sees the effects of T2 but not T1. The Writes Follow Reads guarantee prevents these anomalies.

- Also known as Session Causality.

- If a process reads a value

v, which came from a writew1, and later performs writew2, thenw2must be visible AFTERw1. Once you’ve read something, you can’t change that read’s past. - Writes follow reads is a totally available property. Every node can make progress regardless of network partitions.

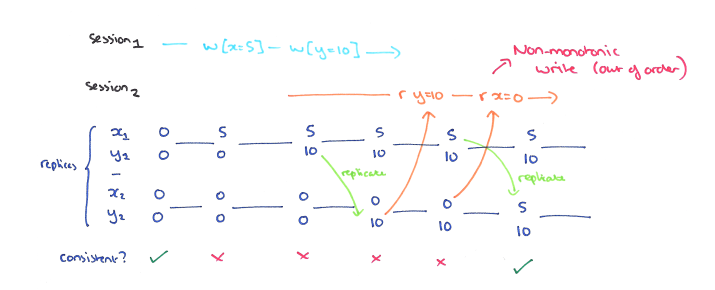

Monotonic Writes

- This guarantees that write operations must go after other writes that reasonably should precede them.

- A non-monotonic write anomaly occurs if a session’s writes become visible out of order.

- If a process performs write w1, then w2, then all processes observe w1 before w2.

- Monotonic writes does not apply to operations performed by different processes, only writes by the same process.

- Monotonic writes can be totally available: even during a network partition, all nodes can make progress.

PRAM

- PRAM stands for Pipeline Random Access Memory.

- A Scalable Shared Memory, which attempts to relax existing coherent memory models to obtain better concurrency.

- It enforces that any pair of writes executed by a single process are observed (everywhere) in the order the process executed them; however, writes from different processes may be observed in different orders.

- PRAM is exactly equivalent to read your writes, monotonic writes, and monotonic reads.

- PRAM is sticky available: in the event of a network partition, all processes can make progress so long as clients always stick to the same server.

- For total availability, we need to sacrifise

Read Your Writes. - This also means Causal consistency is also sticky available.

- Sequenctial consistency is

Unavailable, ie, Not available during some types of network failures. Some or all nodes must pause operations in order to ensure safety.

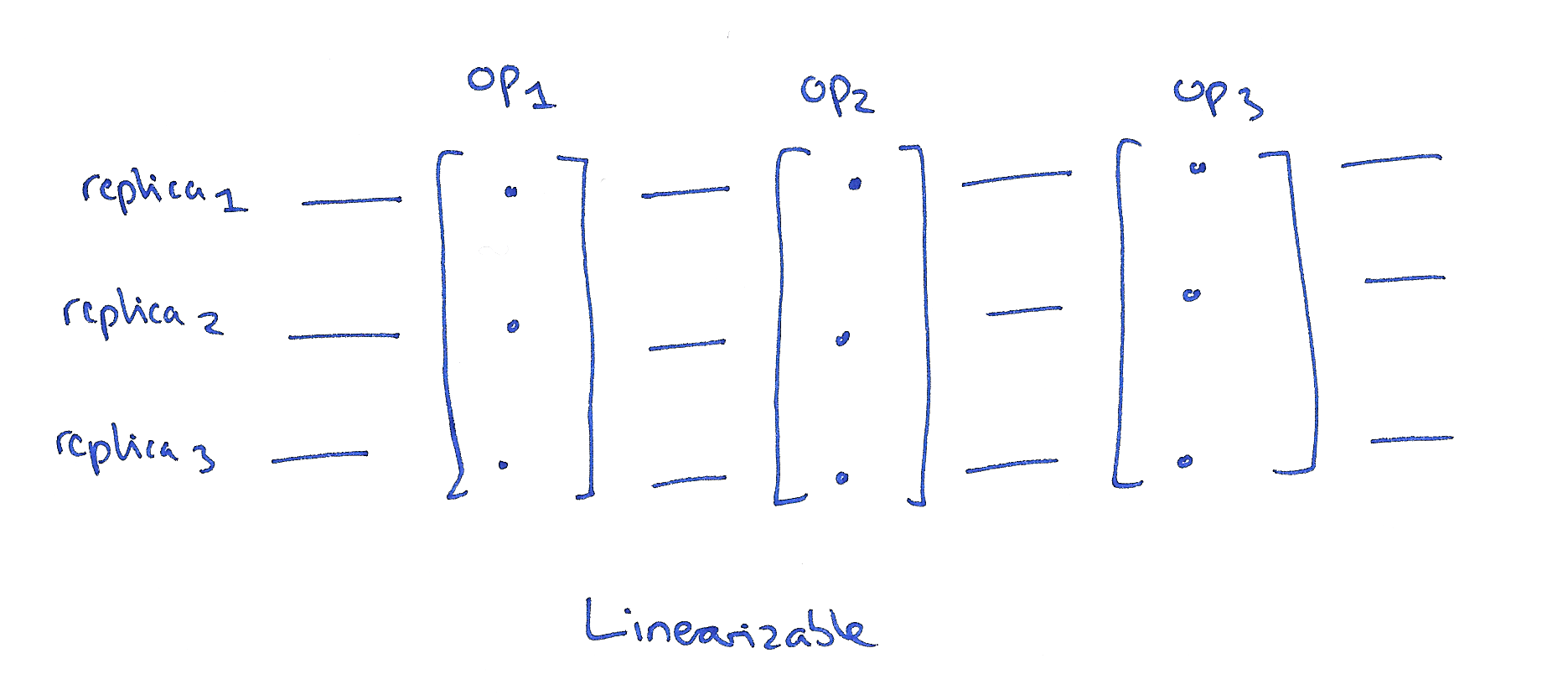

Linearizability

- In the distributed systems community, the gold standard is linearizability.

- Linearizability concerns single operations on single objects.

- A linearizable schedule is one where each operation appears to happen atomically at a single point in time. Once a write completes, all later reads (wall-clock time) should see the value of that write or the value of a later write.

- In a distributed context, we may have multiple replicas of an object’s state, and in a linearizable schedule it is as if they were all updated at once at a single point in time.

- This model cannot be totally or sticky available; in the event of a network partition, some or all nodes will be unable to make progress.

- Also called Atomic Consistency

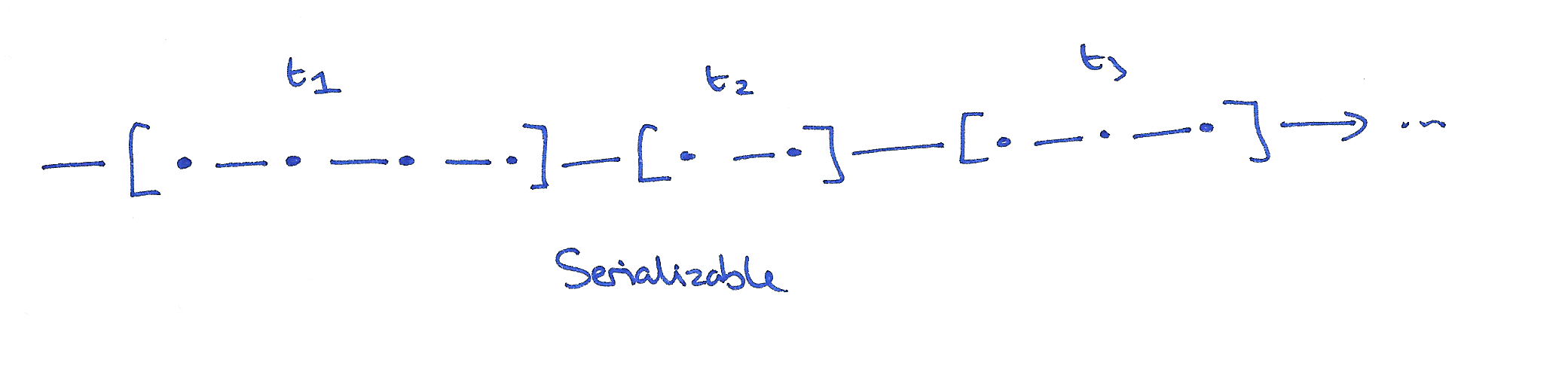

Serializability

- In the database systems community, the gold standard is serializability.

- Informally, serializability means that transactions appear to have occurred in some total order.

- It is also a multi-object property: operations can act on multiple objects in the system.

- Serializability is a transactional model: operations (usually termed “transactions”) can involve several primitive sub-operations performed in order.

- Serializability guarantees that operations take place atomically: a transaction’s sub-operations do not appear to interleave with sub-operations from other transactions.

- It’s the highest form of isolation between transactions.

- Serializability cannot be totally or sticky available

-

Serializability does not require a per-process order between transactions. A process can observe a write, then fail to observe that same write in a subsequent transaction. In fact, a process can fail to observe its own prior writes, if those writes occurred in different transactions.

- Strict serializability is serializability & linearizability combined – the transactions are ordered according to real time. It’s what you’d get if your database had only a single thread and processed transactions one-at-a-time in order of submission on that thread.

References

Written on October 25, 2019